I’ve been in the financial advice business for 36 years. More than half my life. It’s fair to say I’ve learned a few things along the way.

- I started two months before the 1987 share market crash – the largest one-day fall in the history of the Aussie stock market. Much of my first year was spent dealing with distraught clients whose previous advisers were no longer answering the phone. That teaches you a bit.

- I learned early on not to trust the property spruikers, who promise a dream built on a ballooning pile of debt, but aren’t around when the balloon bursts.

- And in those early days as a sponge soaking up information from wherever I could get it, I’d attend lots of fund manager briefings, and soon learned who served the best food afterwards. (It was Jardine Fleming, an Asian-based fund manager no longer around. I hope I didn’t eat them out of business.)

But if I had to nominate the single best piece of advice that I learned, one which I’m very happy to share, it’s this, from my first boss in the industry.

Income Growth = Capital Growth.

Simple and succinct. But it goes to the heart of a plethora of issues, misconceptions, myths and misinformation that swirl around the world of financial advice. How so?

Mostly, if you ask someone why they invest, they’ll say “For Growth”

OK, so what is Growth? How does it happen?

“Well, the price goes up”.

Yes, but why?

Some things go up in value because they are rare, or collectible, or become fads for a while. Which is fine if you’re really knowledgeable about the particular type of thing, like art, stamps or coins. Or if you are lucky, and can wait around for fifty years for your old Alfa Romeo to become sought after. But it’s hardly what you’d use to underpin your retirement cash needs. It is more akin to speculating than investing.

For investors, the answer is income. Businesses make profits and pay dividends. Property earns rent. Bank deposits pay interest.

A business that makes a big profit is worth more than a business that makes a small one. It follows that if the income earned by a business goes up, so will the value. Income growth = capital growth. Watch the income and you can be pretty confident which way the price will go.

The problem is, instead of the income angle, the finance media and large sections of the financial advice community spend all their time talking about day-to-day price movements, as if that is the cause and not the effect.

Maybe it’s because the income story takes a fair while to play out, whereas the media has column space and air time to fill every day. Prices move around every day so there’s always something to write about. “The market was up 1% today”, or “Markets spooked by inflation news” or worse, “Billions wiped off super funds”. Yet over the past 17 years, the market has gone up on 54% of business days and down on 46%, so chances are today’s headline will be redundant by tomorrow.

But in the meantime, this fixation with daily prices promotes the impression that the share market is a risky, volatile place to be – far more so than it really is. This can cause investors to make poor choices and bring unnecessary stress.

The fact is, day traders aside, investors with long term aims, like retirees or those preparing for their retirement, don’t buy and sell every day. So day-to-day price movements are largely irrelevant. What they want is a secure income stream, preferably one that grows, plus a sense that if and when they ever do need to sell something, it will be at a time and price that suits them.

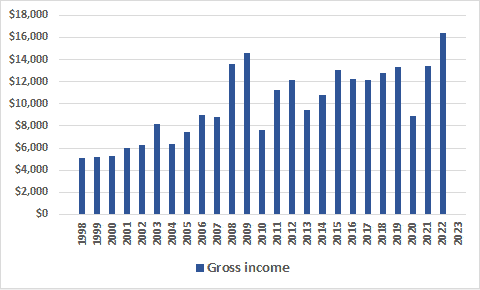

So what’s the truth about shares as an income investment? If you had invested $100,000 across the All Ordinaries Share index at the beginning of 1998, here is the pattern of the annual income you would have received, including franking credits and before tax, over the subsequent 25 years.

There were a couple of blips – the aftermath of the GFC in 2009, and later the COVID year, saw companies pull their heads in a bit with their dividend payments – but they recovered quickly. Overall it’s a pattern of consistent growth, such that by the end of the period, annual income had grown more than three-fold.

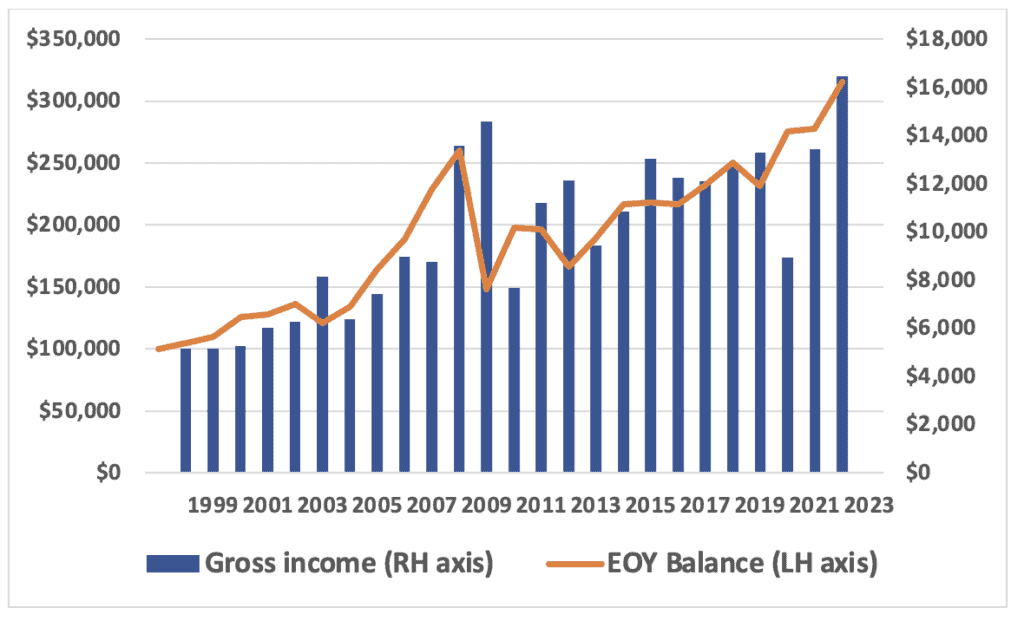

Now let’s superimpose the value of the portfolio – that is, assuming you took all your dividends in cash, what happened to the growth of your portfolio?

Interestingly the $100,000 has also grown more than three-fold. This is no coincidence. As the income stream grows, investors are prepared to pay a higher price to buy into it. Income growth = capital growth.

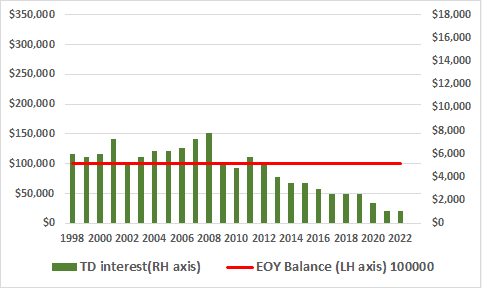

For the record, let’s compare this with how you’d have gone investing in secure bank term deposits over the same period. Let’s say at the start of each of those years you took out a one-year term deposit paying the cash rate of the day + 1%. At the end of each term you rolled it over into another one.

To make it a fair fight, I’ve used the same scales as the shares example. It kind of turns the common wisdom about returns and risk on its head, doesn’t it?

We have plenty more to say on the subject – including how to manage if you do need to draw down on your capital from time to time (See The Simple Truth about Investment Risk for Retirees – and How to Manage it). We have also developed software specifically designed to help manage your long term cash flow position.

To be honest, if I had my time over, as an adviser I’d go a lot harder, louder and stronger on this income growth = capital growth theme. It’s a message that’s easily obscured by the sheer volume of the daily noise, much of which is pointless blather. Certainly any younger advisers (which is most of them these days) who find themselves in my circle will get the same advice my first boss gave me.

All Ordinaries data: www.spglobal.com

Dividend data: Australian Tax Office.

Interest rates data: Australian Bureau of Statistics.